Olivers Insights

Investment outlook Q&A

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

IntroductionInvestment markets continue to be buffeted by multiple uncertainties, but so far returns this year have been okay as shares have climbed the “wall of worry”. This note takes a look at the main

Read More– Inflation, interest rates, recession, the US debt ceiling, geopolitics, house prices and other issues

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

Introduction

Investment markets continue to be buffeted by multiple uncertainties, but so far returns this year have been okay as shares have climbed the “wall of worry”. This note takes a look at the main questions investors commonly have in a simple Q & A format.

Have we seen the peak in inflation?

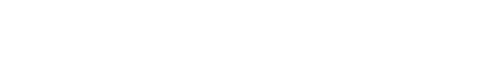

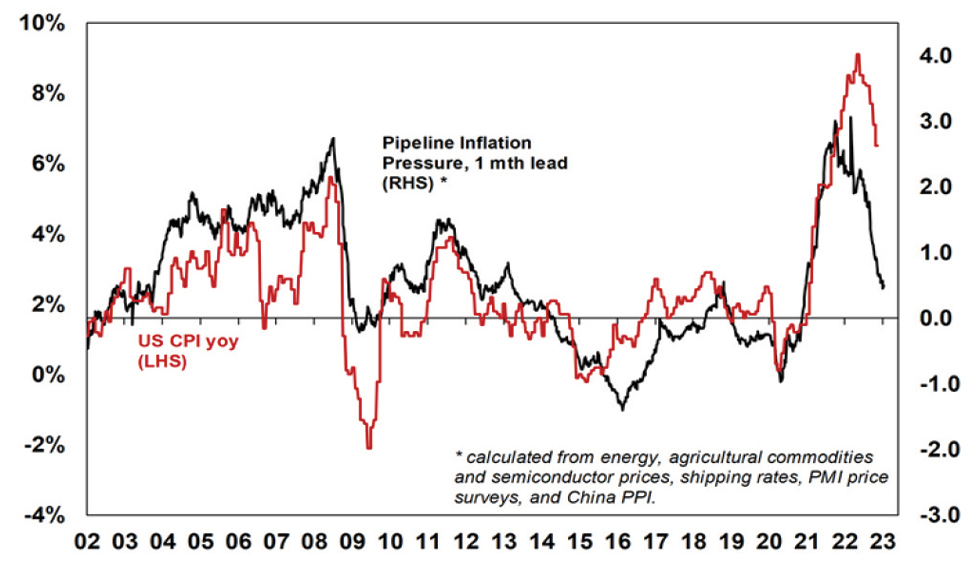

Inflation is still too high but it looks to have peaked. US inflation led on the way up and it looks to be leading on the way down. It has fallen to 5%yoy from a high of 9.1% in mid last year. Supply bottlenecks have improved, freight costs have fallen and slowing demand is reducing demand side inflation. While core services inflation excluding shelter remains sticky it is starting to slow, shelter (or rent) inflation also looks to have peaked and our US Pipeline Inflation Indicator continues to point to lower inflation.

AMP Pipeline Inflation Indicator

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

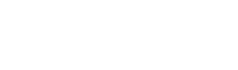

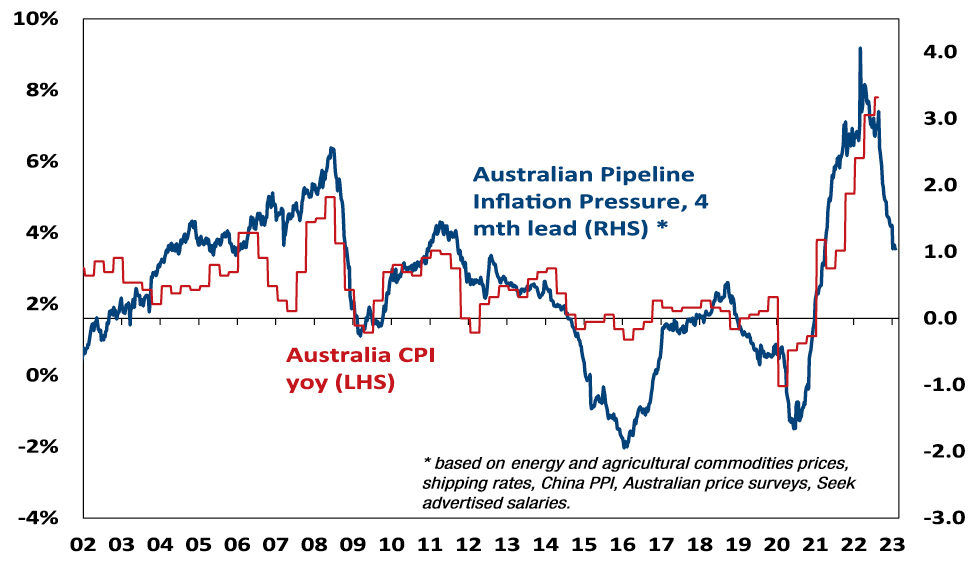

In Australia, inflation is lagging the US by about six months and looks to have peaked in the December quarter. There is likely more upside in electricity prices and rents, and based on the US experience underlying measures of inflation may take a bit longer to peak. However, the ABS’ Monthly CPI Indicator fell back to 6.8%yoy in February from a high of 8.4% in December and our Australian Pipeline Inflation indicator points to a further fall in inflation ahead.

Australia Pipeline Inflation Indicator

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

What impact will US banking strains have?

Quick action by US and Swiss authorities have settled the banking problems seen in March. However, the banking strains likely have further to run as tighter monetary policy impacts borrowers & hence the quality of loans and the banking strains look to have increased bank funding costs and pressure on margins and appears to be resulting in tighter lending standards. Estimates of its impact by the Fed range from being equivalent to 0.25%-1.5% of Fed rate hikes. So it should take pressure off the Fed.

Are central banks nearly done?

The combination of easing inflation pressures, the defacto monetary tightening flowing from banking strains in the US and Europe and increasing evidence of cooling economies and labour markets suggests that major central banks are at or close to the top on interest rates:

-

Several central banks have paused monetary policy tightening in the last month or so – including the RBA, Bank of Canada, Bank of Korea and the Singapore Monetary Authority.

-

The ECB has continued to tighten but has softened its tightening bias.

-

The sticky core US inflation evident in March likely leans the Fed towards one last 0.25% rate hike at its May meeting. But with falling job openings, a mixed jobs report for March, rising jobless claims the minutes from the last Fed meeting indicating that the Fed’s staff expect bank stress to contribute to a “mild recession” it’s a close call.

-

In Australia, with the labour market being a lagging indicator and economic growth and inflation likely to continue to slow our view is that we are either at or very close to the peak in rates ahead of cuts later this year or early next. Another hike in May is still a very high risk though – as still strong jobs data has added to the risk of a wages breakout and the upswing in the property market if sustained could reverse the negative wealth effect from lower home prices. March quarter inflation data will be watched closely.

What is the risk of recession?

While the risk of recession has receded in Europe (with lower gas prices) it remains high in the US with various leading indicators – including inverted yield curves (where short term interest rates are above longer term yields) – warning of a high risk of US recession in the next 6-12 months. Over the last 50 years all US recessions have been preceded by inverted yield curves as is the case now – but the lag can be up to 18 months and it can give false signals. However, if the Fed soon stops tightening a US recession could still be averted or it could be mild which would limit further downside in US shares. In Australia, the risk of recession is high. But our base case is that it will be avoided thanks to strong business investment, Chinese reopening and providing the RBA soon stops hiking. Economic growth will still slow to a crawl this year though.

Have geopolitical threats faded?

These have increased in recent years with the loss of global faith in liberal democracy and relative decline of US giving rise to a multipolar world. So far this year geopolitical issues have not had a major impact on markets, helped by the absence of significant elections in major countries and the stalemate in Ukraine. But risks remain around China and Taiwan, Iran’s progress towards nuclear weapons, Russia/Ukraine and the possible return of Trump in next year’s US election.

How big a problem is the US debt ceiling?

The US Congress imposes a ceiling on Government debt that needs to be raised every so often given its ongoing budget deficit. If it’s not raised once reached spending would have to be slashed back to the level of revenue – leading to a 5% or so hit to GDP and talk of default on its commitments. As we saw in 2011 and 2013 raising it can lead to brinkmanship as fiscally conservative Republicans seek to reduce the budget deficit and as always Washington leaves things to the last minute to resolve. Back then it was resolved but only in the nick of time and after investment markets fell sharply. The process then caused damage to Republican’s political standing so in subsequent years it was resolved relatively smoothly. However, with Republican’s regaining control of the House of Representatives and demanding a commitment to spending cuts it looks like it will be an issue again this year. The US has already hit its debt ceiling but cash balances mean it can probably hold out to mid-year or the third quarter without needing to raise it. Raising it will be a long process where the House passes a bill with spending cuts that’s rejected by the Senate and Biden ahead of inevitable negotiations at some point. But any resolution will again be last minute, and markets will fret at the prospect of no deal and a default causing the potential for share markets falls at the time. The odds are a deal will be reached enabling shares to rebound or Republican’s will get the blame for any default and big cuts to spending which won’t look good for them ahead of next year’s election.

Are bonds dead as a portfolio diversifier?

Last year saw both shares and bonds sell off leading many to question the role of bonds as a portfolio diversifier to equity volatility. However, last year’s poor performance from bonds and shares together was driven by a common driver of inflation. This is not that unusual historically when the surge in inflation in the 1970s and then its collapse in the 1980s into the early 1990s boosted the correlation between them. However, with bond yields now higher and inflation falling bonds are likely now to provide a better diversifier to equities should equities be hit by recession risks.

Will high levels of global debt de-rail things?

This is now estimated to be up around $US300trn or nearly 350% of GDP globally and clearly poses a risk with interest rates rising, particularly in emerging countries with $US debt. However, much of the rise in debt since the pandemic has been in the public sector where the risk of major problems is less (as governments can raise taxes) and high debt levels may make central banks jobs easier as they won’t have to raise rates as much as otherwise to slow down spending and hence inflation.

Have Australian house prices already bottomed?

From their low in February, average dwelling prices in the five biggest capital cities are up 1.3% led by Sydney which is up 2.6%. This appears to reflect bargain hunters, first home buyers and investors stepping in after sharp falls, expectations that mortgage rates have peaked, the return of immigrants and low listings. Our base case remains for Australian home prices to fall further out to later this year as interest rate hikes impact and slower economic growth impact. The RBA estimates that 40% of home borrowers have less than 3 months prepayment buffers, 15% of variable rate borrowers will have negative cash flow by year end if the cash rate rises to 3.75% and nearly 900,000 fixed rate mortgages are due to reset to interest rates that are more than double their initial level. This all runs the risk of increased distressed sales, particularly as growth slows. But the rapid return of immigration, very low rental vacancy rates & constrained supply mean that our expectation for a top to bottom fall of 15-20% may be too pessimistic and we may have already seen the low. So given the conflicting forces at present the property market has become hard to call.

How can we improve housing affordability?

The resurgence of immigration, record low rental vacancy rates, still very high home price to income and debt to income ratios and surging rents have all refocussed attention on poor housing affordability in Australia. Fixing this requires a multifaceted solution across all levels of government with targets to be achieved over say a five-year period. My list of policies to improve affordability includes:

-

Measures to boost new supply – relaxing land use rules within reason, releasing land faster and speeding up approval processes.

-

Matching the level of immigration to the ability to supply housing. The pandemic driven pause in immigration provided a perfect opportunity to get this right upon reopening but we botched it yet again.

-

Encouraging greater decentralisation – the “work from home” phenomenon shows this is possible, but it should be helped along with infrastructure and measures to boost regional housing supply. Excess CBD office space should be converted to residential.

-

Tax reform – to replace stamp duty with land tax (to make it easier for empty nesters to downsize & cutting the upfront burden for first home buyers), cut the capital gains tax discount (to end a distortion favouring speculation) and to encourage build to rent property.

What is the risk of commercial property slump?

Commercial property benefitted like other assets from the search for yield as bond yields plunged in the decades into the pandemic providing a positive valuation effect. Some saw the asset class as a replacement for bonds in portfolios. However, its now vulnerable from the double whammy of the rise in bond yields driving a negative valuation effect at the same time as reduced space demand flowing from “work from home” in the case of office property and online retail in the case of retail property. Of these threats, the first looks more manageable as commercial property still offers a reasonable (but lower) risk premium over bonds but the second is more significant. An economic downturn would add to the threat. The experience of the early 1990s where office valuations fell for 3 years as oversupply & recession pushed vacancy rates to 20-30% warns that commercial property slumps can be drawn out.

Source: AMP Capital April 2023

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.

Five charts on investing to keep in mind in rough times like now

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

IntroductionEvery so often the degree of uncertainty around investment markets surges and that’s been the case for more than a year now reflecting the combination of high inflation, rapid interest rate hikes, the high and rising risk of recession which has been added to in the last few

Read MoreDr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

Introduction

Every so often the degree of uncertainty around investment markets surges and that’s been the case for more than a year now reflecting the combination of high inflation, rapid interest rate hikes, the high and rising risk of recession which has been added to in the last few weeks by problems in US and European banks. And all of this has been against the background of increased geopolitical uncertainties. Falls in the value of share markets and other investments can be stressful as no one wants to see their wealth decline. And so when uncertainty is high a natural inclination is to retreat to perceived safety. As always, turmoil around investment markets is being met with much prognostication, some of which is enlightening but much is just noise. I will be the first to admit that my crystal ball is even hazier than normal in times like the present. As the US economist JK Galbraith once said “there are two types of economists – those that don’t know and those that don’t know they don’t know.” And this is certainly an environment where we need to be humble.

But while history does not repeat as each cycle is different, it does rhyme, in that each cycle has many common characteristics. So, while each cycle is different the basic principles of investing still apply. This note revisits once again five charts I find particularly useful in times of economic and investment market stress.

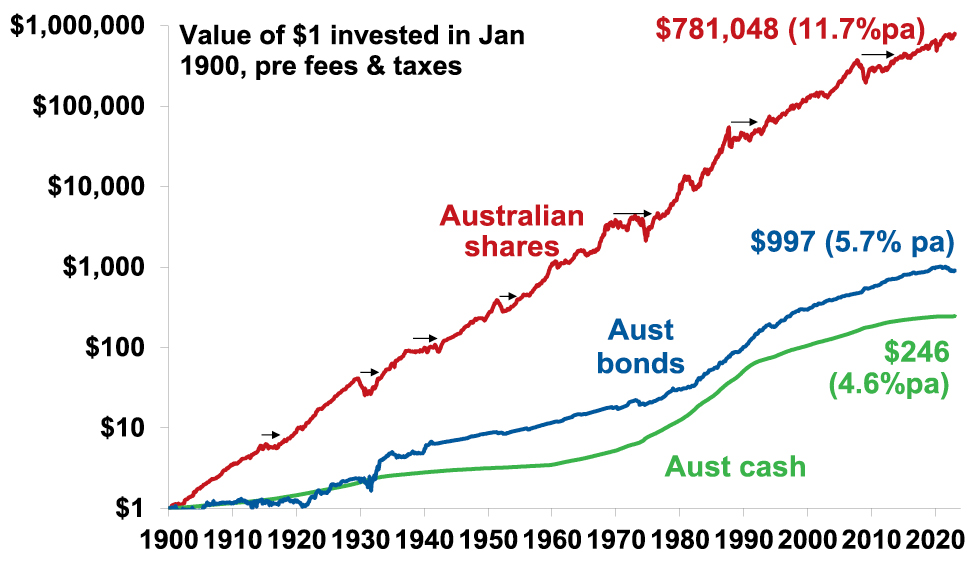

Chart #1 The power of compound interest

This is my favourite chart. It shows the value of $1 invested in various Australian assets in 1900 allowing for the reinvestment of dividends and interest along the way. That $1 would have grown to $246 if invested in cash, to $997 if invested in bonds and to $781,048 if invested in shares up until the end of February. While the average return since 1900 is only double that in shares relative to bonds, the huge difference between the two at the end owes to the impact of compounding – or earning returns on top of returns. So, any interest or return earned in one period is added to the original investment so that it all earns a return in the next period. And so on. I only have Australian residential property data back to 1926 but out of interest it shows (on average!) similar long term compounded returns to shares.

Shares versus bonds & cash over very long term – Australia

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

Key message: to grow our wealth, we must have exposure to growth assets like shares and property. While shares and property have had a rough ride over the last year as interest rates surged, history shows that both will likely do well over the long-term.

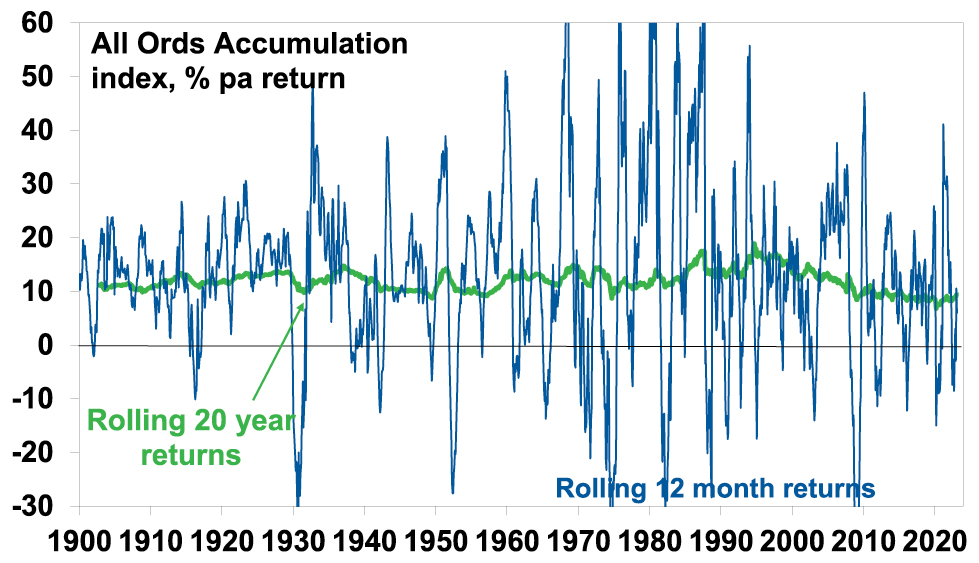

Chart #2 Don’t get blown off by cyclical swings

The trouble is that shares can have lots of (often severe) setbacks along the way as is evident during the periods highlighted by the arrows on the previous chart. Even annual returns in the share market are highly volatile, but longer-term returns tend to be solid and relatively smooth, as can be seen in the next chart. Since 1900, for Australian shares roughly two years out of ten have had negative returns but there are no negative returns over rolling 20-year periods.

Australian share returns over rolling 12 mth & 20 yr periods

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

The higher returns that shares produce over time relative to cash and bonds is compensation for the periodic setbacks they have. But understanding that these periodic setbacks are just an inevitable part of investing is important in being able to stay the course and get the benefit of the higher long-term returns shares and other growth assets provide over time.

Key message: short-term, sometimes violent swings in share markets are a fact of life but the longer the time horizon, the greater the chance your investments will meet their goals. So, in investing, time is on your side and it’s best to invest for the long-term when you can.

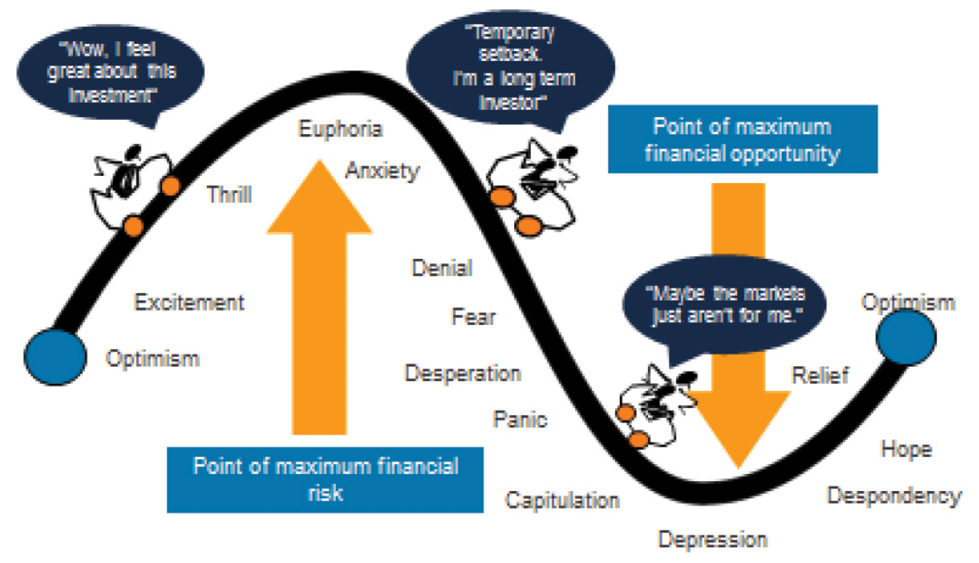

Chart #3 The roller coaster of investor emotion

It’s well known that the swings in investment markets are more than can be justified by moves in investment fundamentals alone – like profits, dividends, rents and interest rates. This is because investor emotion plays a huge part. This has been more than evident over the last year with all the swings in markets. The next chart shows the roller coaster that investor emotion traces through the course of an investment cycle. Once a cycle turns down in a bear market, euphoria gives way to anxiety, denial, capitulation and ultimately depression at which point the asset class is under loved and undervalued and everyone who is going to sell has – and it becomes vulnerable to good (or less bad) news. This is the point of maximum opportunity. Once the cycle turns up again, depression gives way to hope and optimism before eventually seeing euphoria again.

The roller coaster of investor emotion

Source: Russell Investments, AMP

Key message: investor emotion plays a huge role in magnifying the swings in investment markets. The key for investors is not to get sucked into this emotional roller coaster. Of course, doing this is easier said than done, which is why many investors end up getting wrong footed by the investment cycle.

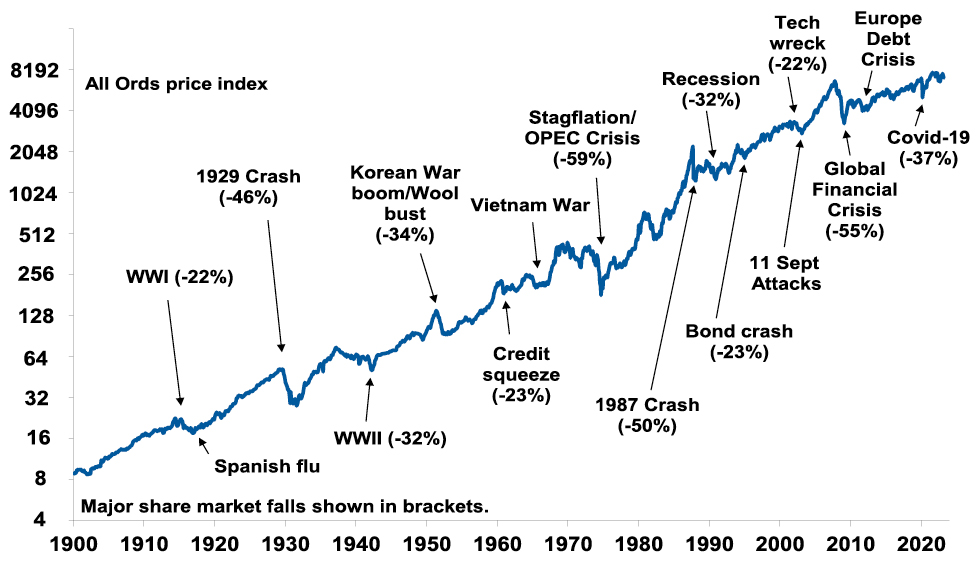

Chart #4 The wall of worry

There is always something for investors to worry about it seems. And in a world where social media is competing intensely with old media it all seems more magnified and worrying. This is arguably evident again now in relation to uncertainty about inflation, interest rates and associated recessions risks. The global economy has had plenty of worries over the last century, but it got over them with Australian shares returning 11.7% per annum since 1900, with a broad rising trend in the All Ords price index as can be seen in the next chart, and US shares returning 9.9% pa. (Note that this chart shows the All Ords share price index whereas the first chart shows the value of $1 invested in the All Ords accumulation index, which allows for changes in share prices and dividends.)

Key message: worries are normal around the economy and investments and sometimes they become intense – like now. But they eventually pass.

Australian shares have climbed a wall of worry

Source: ASX, AMP

Chart #5 Timing is hard

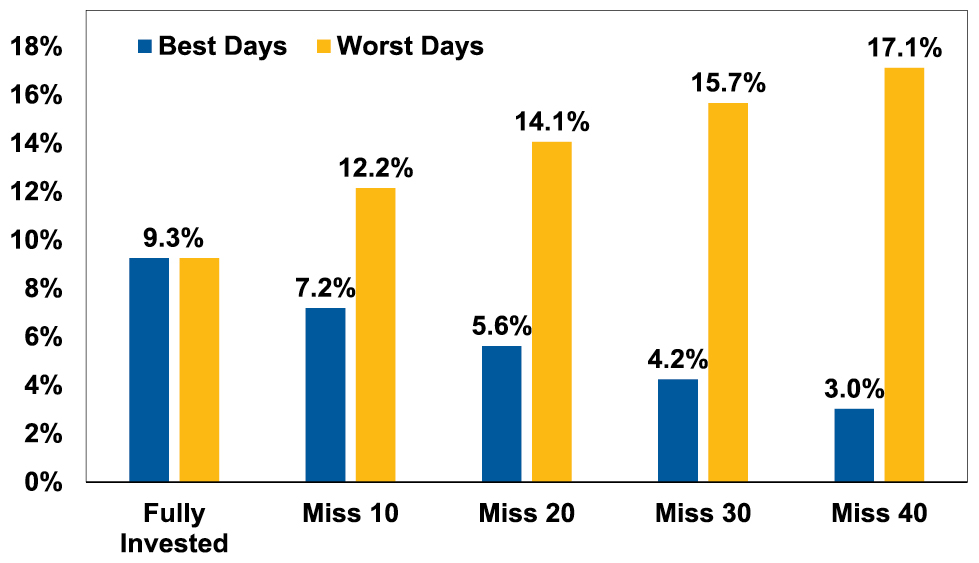

The temptation to time markets is immense. With the benefit of hindsight many swings in markets like the tech boom and bust and the GFC look inevitable and hence forecastable and so it’s natural to think why not switch between say cash and shares within your super fund to anticipate market moves. This is particularly the case in times of emotional stress like now when much of the news around inflation, interest rates and recession risks seem bad. Fair enough if you have a process and put the effort in. But without a tried and tested market timing process, trying to time the market is difficult. A good way to demonstrate this is with a comparison of returns if an investor is fully invested in shares versus missing out on the best (or worst) days. The next chart shows that if you were fully invested in Australian shares from January 1995, you would have returned 9.3% pa (with dividends but not allowing for franking credits, tax and fees).

Missing the best days and the worst days

Return on Australian shares, % pa (All Ords Accumulation Index, 1995-2023)

Covers Jan 1995 to 17 March 2020. Source: Bloomberg, AMP

If by trying to time the market you avoided the 10 worst days (yellow bars), you would have boosted your return to 12.2% pa. And if you avoided the 40 worst days, it would have been boosted to 17.1% pa! But this is very hard, and many investors only get out after the bad returns have occurred, just in time to miss some of the best days. For example, if by trying to time the market you miss the 10 best days (blue bars), the return falls to 7.2% pa. If you miss the 40 best days, it drops to just 3% pa.

Key message: trying to time the share market is not easy. For most its best to stick to an appropriate well thought out long term investment strategy.

Source: AMP Capital March 2023

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.

Have Australian home prices bottomed? Probably not.

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

IntroductionFrom their high in April to their low last month national average home prices have fallen 9.1% making it their biggest fall in CoreLogic records going back to 1980. Capital city average prices were down 9.7% which is their second biggest fall, after the 10.2% fall in 2017-19.

Read MoreDr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

Introduction

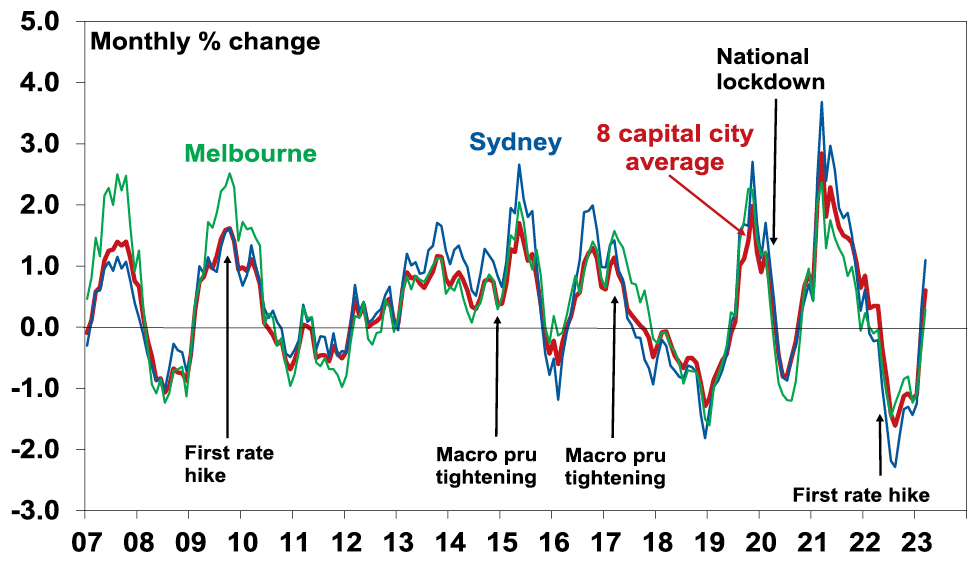

From their high in April to their low last month national average home prices have fallen 9.1% making it their biggest fall in CoreLogic records going back to 1980. Capital city average prices were down 9.7% which is their second biggest fall, after the 10.2% fall in 2017-19. However, average price falls had slowed to a crawl and CoreLogic data shows that this has morphed into price gains across several cities so far in March with Sydney prices tracking up 1.1% at a monthly rate and five capital city average prices tracking up 0.6%. See the next chart. If home prices have bottomed this would leave them short of our expectation for a 15-20% top to bottom fall. So are property prices doing it again? – falling less than expected and then rising more than expected. This note looks at the positives and negatives for the residential property market outlook.

Average capital city home prices

Source: CoreLogic, AMP

The positives for the property market

Here are the main positives for the property market.

-

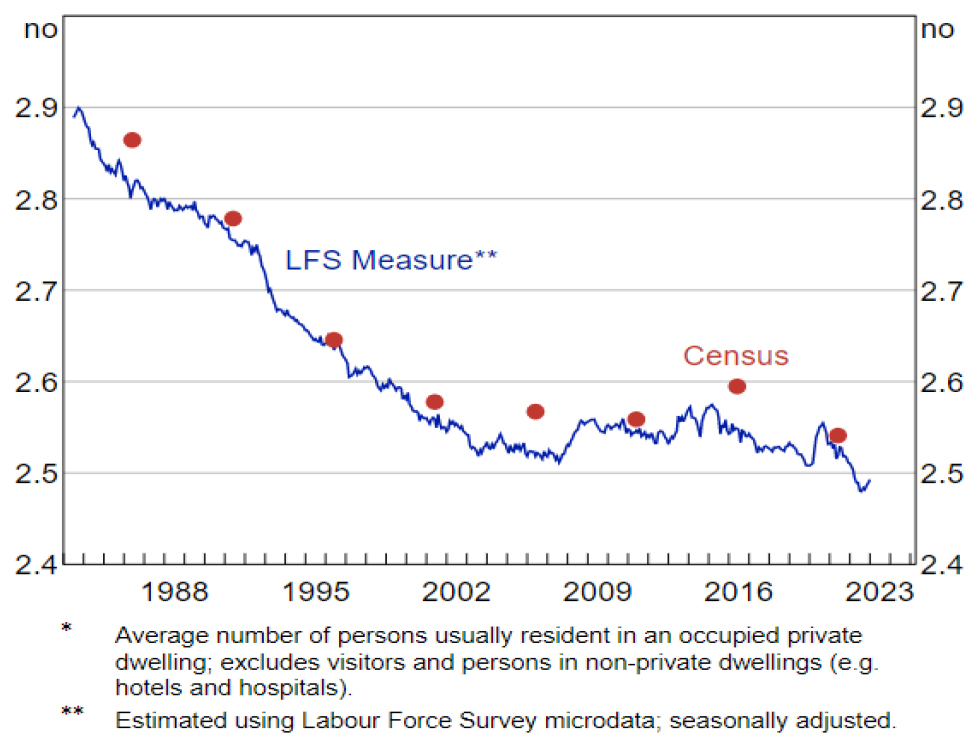

RBA analysis shows a decline in household average household size since the start of 2020 of around 1%, which it estimates has added around 120,000 households to underlying dwelling demand partly offsetting the negative impact on demand from the hit to immigration through the pandemic lockdown.

Average Household Size*

Source: RBA Bulletin, March 2023, based on ABS data

-

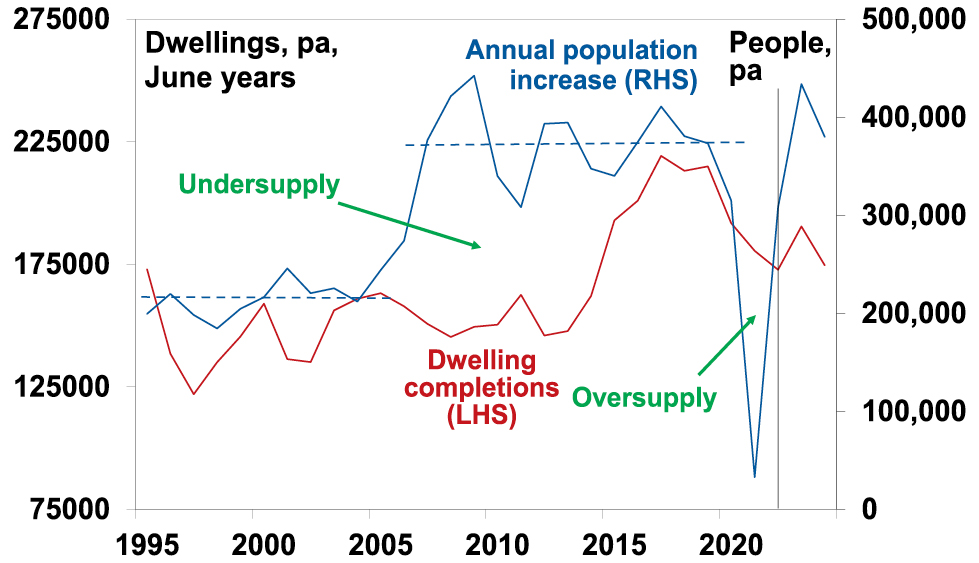

Immigrants are returning boosting underlying demand for housing. Net immigration was around 320,000 last year up from just 5940 in lockdown impacted 2021. This roughly equates to demand for an extra 125,000 dwellings. Its likely to remain strong this year. This is seeing a rise in the cumulative undersupply of housing again.

Home construction versus population growth

Source: ABS, AMP

-

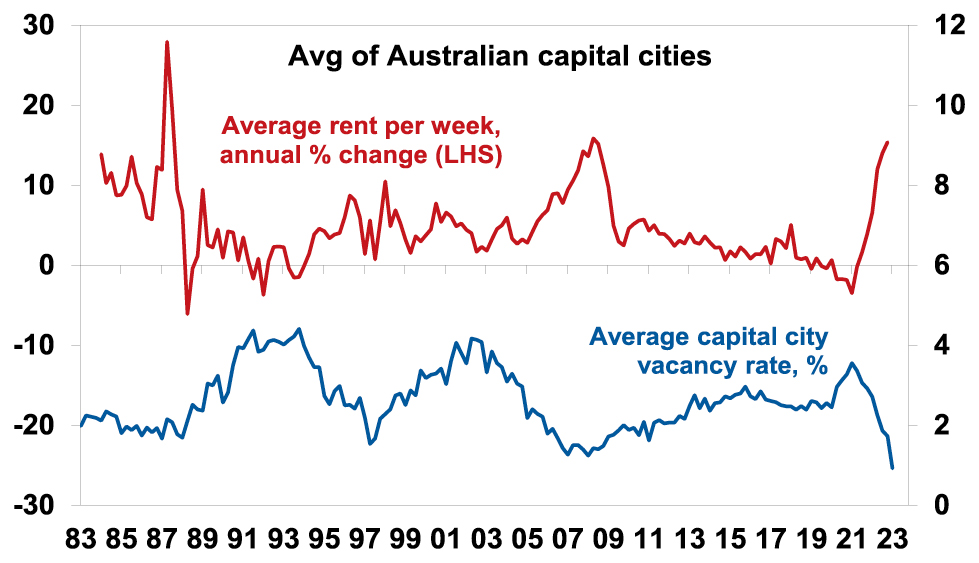

Partly reflecting this, capital city rental vacancy rates below 1% are driving a surge in rents. This should be positive for investor demand.

Falling vacancy rates, rising rents

Source: REIA, Domain, AMP

-

The record plunge in home prices and high inflation have pushed real home prices from well above their long term trend to back in line. This may have attracted bargain hunters back into the market given the past experience of price falls being quickly followed by rebounds.

-

Allowing first home buyers to opt for land tax in NSW and other government support programs will be boosting demand.

-

Listings are very low, running around 25-30% down on a year ago.

-

Our assessment is that we are at or close to the top on interest rates and the problems in global banks add support to this assessment.

-

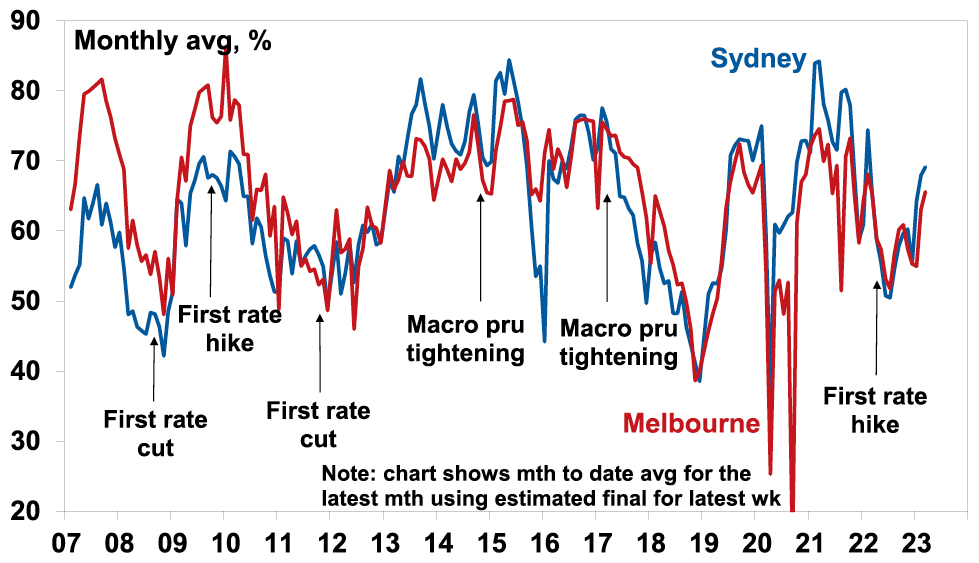

Auction clearance rates have improved from their lows, and they usually have a directional correlation with home prices.

Auction clearance rates

Source: Domain, AMP

So maybe the combination of bargain hunters motivated by the historical record that shows prices rebounding quickly, low listings, backed by expectations for strong demand as immigrants return are driving a recovery in prices. More fundamentally, the ongoing supply short fall provides some sort of floor under prices.

The negatives for the property market

However, the headwinds facing the property market are significant:

-

The full impact of variable rate hikes has yet to be fully felt as it takes 2-3 months for RBA hikes to show up in actual mortgage payments;

-

Roughly 880,000 fixed rate loans will expire this year which will see mortgage rates reset from around 2% to around 5 or 6%. RBA analysis indicates that while fixed rate borrowers may have similar liquid assets to variable rate borrowers they have higher risk characteristics;

-

While we think rates are at or close to peaking numerous economists still see the cash rate rising above 4%;

-

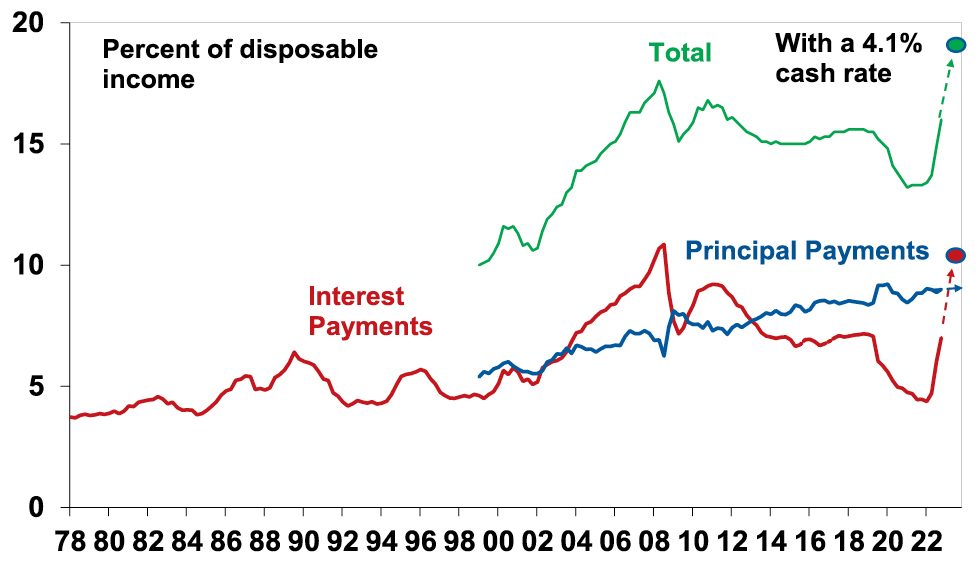

Household debt servicing payments as a share of income have already risen to their highest in more than a decade resulting in a large squeeze on household cashflows but will rise further given the lagged flow through of variable rates and the fixed rate reset. A rise in the cash rate to 4.1% would see them pushed to record levels. This will remove roughly 5% of household cashflow in relation to income.

Household principal and interest payments relative to disposable income

Source: ABS, BIS, AMP

-

Australian economic conditions will deteriorate this year as weaker global growth impacts demand for our exports, rate hikes bear down on domestic demand as pent up demand from the pandemic is exhausted & this all combines to push up unemployment. Higher unemployment will likely add to mortgage stress.

-

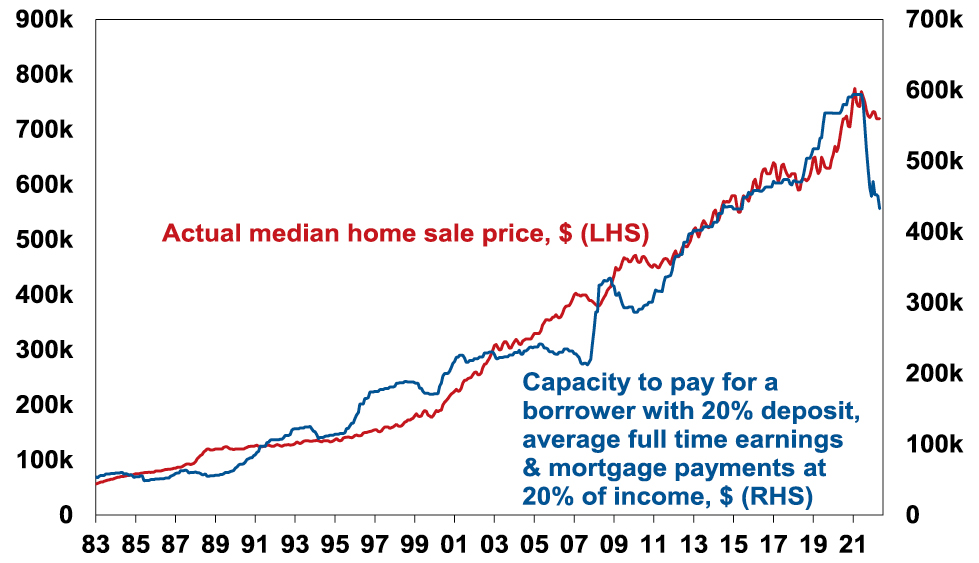

The hit to home buying capacity from rate hikes – of around 27% for a buyer with a 20% deposit and average full-time earnings – remains even if rates have stopped rising. See the next chart.

Australian Average Home Prices

Source: RBA, CoreLogic, AMP

-

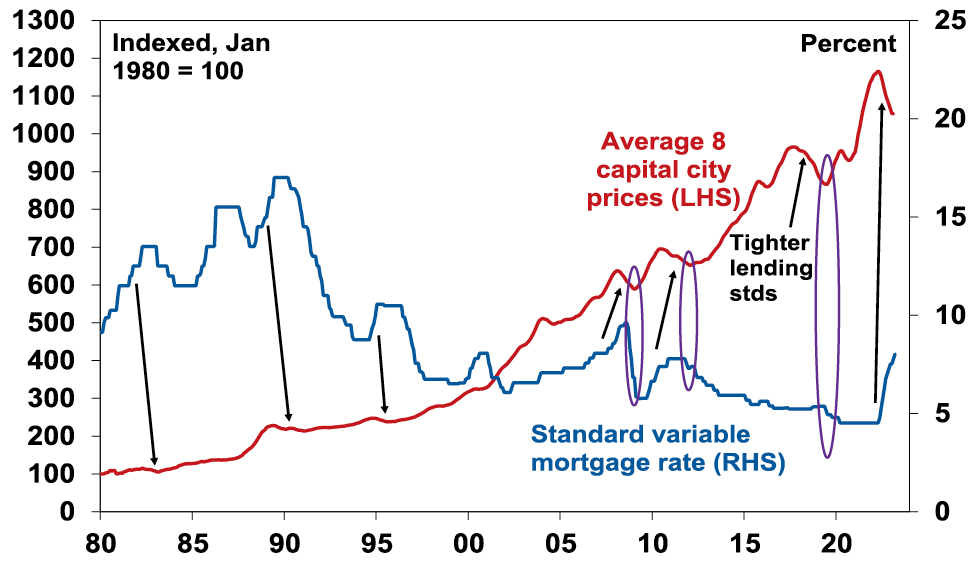

Property down cycles into 2009, 2012 and 2019 only saw prices sustainably bottom once interest rates started falling. See the purple ovals in the next chart. And rate cuts are still a way off yet.

Australian property prices and interest rates

Source: CoreLogic, RBA, AMP

The combination will likely constrain demand and cause a potential increase in supply as some financially stressed homeowners sell.

Our base case

Our base case remains that the current bounce in home prices will be short lived as demand from bargain hunters runs its course, the impact of higher interest rates reasserts itself and listings increase in response to distressed selling. So we continue to see average home prices having a top to bottom fall of 15-20% to later this year of which we are half way through, and we don’t see a sustained recovery until next year.

While Australia’s fundamental housing shortage is now reasserting itself again – with rising underlying demand on the back of returning immigration and insufficient supply as evident in very low rental vacancy rates – it was the shift to ever lower interest rates over many years into the pandemic that allowed the supply shortfall to drive ever higher home price to income ratios over the last few decades. Now higher interest rates make this more difficult suggesting that the supply shortfall should take place at lower price to income ratios.

However, the current environment is very hard to read, so there is a chance that prices have bottomed, particularly if rates have peaked and if the Australian economy has a soft landing. But even if this is the case, in the absence of much lower interest rates the recovery is likely to be constrained as buyer capacity to pay for homes will be constrained.

Source: AMP Capital March 2023

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.

Shares hit another bout of turbulence – US banks, inflation, interest rates and recession risk

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

IntroductionShares have hit turbulence again with worries about inflation, interest rates, recession and, now, problems in US banks. After rallying strongly at the start of the year the US share market has reversed much of its year to date gain leaving it down

Read More– what it means for investors?

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

Introduction

Shares have hit turbulence again with worries about inflation, interest rates, recession and, now, problems in US banks. After rallying strongly at the start of the year the US share market has reversed much of its year to date gain leaving it down 20% from its January high last year and at risk of a retest of its October lows when it was down 25%. Non-US shares are holding up better with Eurozone shares down by 7% & Australian shares also down 9% from their record highs but are vulnerable to moves in US shares. This note looks at the key worries and what it means for investors.

Are we going to see systemic problems in US banks?

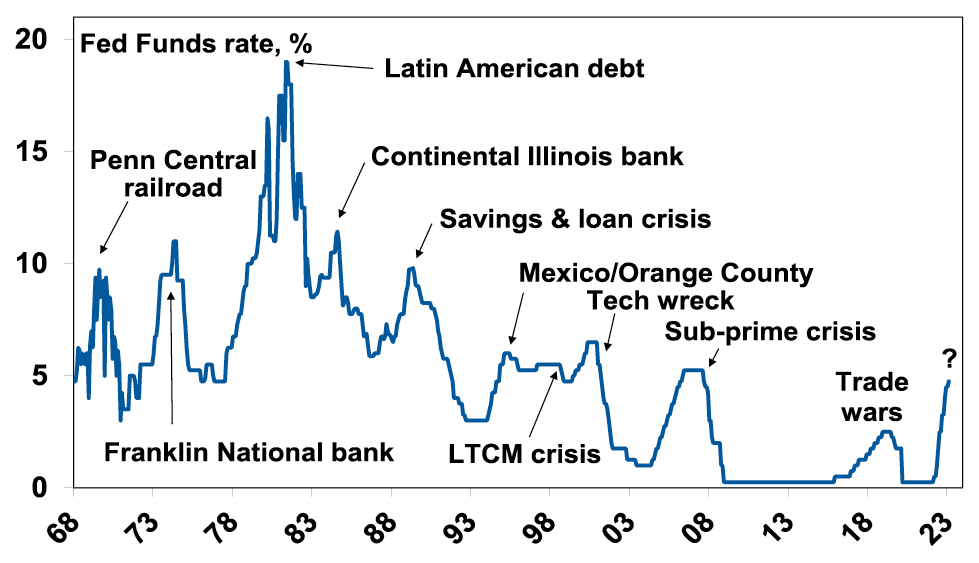

Three regional US lenders have collapsed or closed in recent days. Silicon Valley Bank, which had a deposit base from tech (and some crypto) companies and customers, collapsed after running into trouble as deposits were withdrawn in the face of tough conditions in the tech and crypto sectors. Silvergate Capital & Signature Bank, crypto friendly banks, also closed after they were made vulnerable after the collapse of FTX crypto exchange. These closures have led to concerns they may reflect the start of broader problems in US banks. This is quite possible as Fed rate hiking cycles by tightening financial conditions invariably trigger financial stresses – think the tech wreck and GFC. See the next chart.

That banks exposed to tech and crypto either for deposits or lending are in trouble is not surprising as both sectors benefitted from the pandemic and easy money but have been hard hit by reopening and rate hikes. And its made worse where banks have concentrated investments in long term bonds which have fallen in value as SVB did – so if they have to sell them to meet withdrawals it’s at a loss. For example, there are reported to be $US620bn of unrealised losses on securities at US banks – of course it’s only a problem if they have to sell them. But at this stage it’s too early to know if problems at these lenders reflect isolated problems in the tech & crypto sectors they’re exposed to, made worse by undiversified deposit bases & concentrated holdings of bonds that have fallen in value or are a sign of a broader problem in the US financial system.

Fed tightening cycles usually end in a circle

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

Fortunately, there are some reasons to suggest that worst case scenarios involving a flow on more broadly in the US and beyond may be limited:

-

US authorities have moved quickly to guarantee deposits (beyond the $US250,000 usually covered by deposit insurance) and the Fed has unveiled a Term Funding Facility that enables banks to borrow cheaply from the Fed in order to avoid selling their bonds at a loss. This should help reduce the risk of runs on banks and avoid a fire sale of bonds. And it should help minimise bigger problems for companies that had deposits at these banks – like layoffs & not paying creditors.

-

Following the GFC large US banks now have to maintain large capital buffers, have less risky exposures or at least less concentrated asset exposures and have more diverse deposit bases than regional banks. Unfortunately, restrictions were eased for smaller banks in 2018.

-

It should also be remembered that US regional bank failures are common – there were 8 in 2018-20 – albeit they were much smaller.

-

All Australian banks are required post GFC to maintain much stronger capital buffers and have tougher restrictions in terms of what they can invest in. They also have very diverse deposit bases so are less at risk of high deposit withdrawals than regional US banks. And they won’t have as much exposure to the vulnerable tech and crypto sectors. And Australian bank deposits are implicitly (if not explicitly) protected. But of course, they are vulnerable to defaults by Australian home borrowers particularly if the property market falls precipitously.

However, it will take a while to determine the full impact and for the dust to settle. And either way banks are likely to see a tougher environment ahead as growth slows and higher rates cause more financial stress for borrowers. It probably also means even tighter lending conditions for tech and crypto and for illiquid businesses like private equity and commercial property. And it’s a sign that Fed tightening has got traction!

But what about inflation?

As indicated in the chart above, past financial crisis in the US have resulted in an end to Fed tightening cycles. At this point its not clear that we are seeing a full-blown crisis unfold or not and high inflation is a bit of a barrier on what the Fed can do. As a result, so far it’s just gone down the path of making it easier for banks to access cheap funding so they don’t have to sell bonds at a loss. But how far the Fed and other central banks can support economies will at least partly be impacted by inflation.

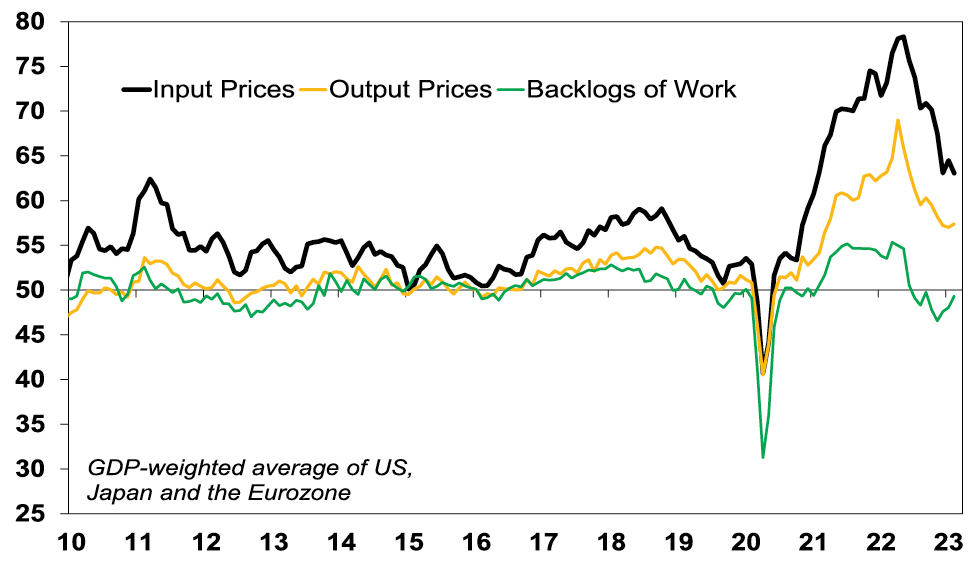

Right now, it’s too high but it looks to have peaked. US and Canadian inflation peaked around mid-last year, inflation in Europe later last year. Australian inflation likely peaked in December. Supply bottlenecks have improved, freight costs have fallen and slowing demand will reduce demand side inflation. As is often the case goods price inflation is leading with services price inflation more sticky reflecting still tight labour markets – but these are showing signs of rolling over with job openings according to Indeed rolling over in the US, Europe and Australia. Wages growth is a key driver of services inflation – but in the US it looks to be slowing & in Australia there are no signs of a wages blowout. Easing inflation pressure is reflected in a declining trend in business surveys with respect to input and output prices and work backlogs & delivery times have fallen to normal levels. See the next chart. And if US bank sector problems depress economic activity, it will put more downwards pressure on inflation.

G3 Composite PMI & Price Pressure

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

Does this mean central banks are nearly done?

If we are right and inflation will fall going forward, albeit with bumps along the way, then central banks are at or near the top and will have more flexibility to respond to financial crisis like the issues now in the US. Indeed, the US banking problems with the risk of a flow on to other countries (where banks also have losses on their bond portfolios) may put pressure on other central banks to provide liquidity support.

-

The ECB is lagging and has further to go than other central banks on rate hikes – but US problems may cause it to slow down.

-

The Bank of Canada has held rates at 4.5% at looks to have peaked.

-

The Fed has been signalling more rate hikes ahead following a recent run of stronger data – but leading US indicators point to slower demand with a high risk of recession (which would slow inflation) and there are tentative signs that the US jobs market is slowing. Bank problems – with the risk of more to come – should help slow the Fed at least heading off a 0.5% hike next week. Our base case is a 0.25% hike but if banking stresses remain high it’s likely to pause. In fact, based on past Fed hiking cycles the collapse in the US 2 year bond yield below the Fed Funds rates suggests the Fed is done!

-

The RBA has become less hawkish & has opened the door to a pause if data shows further cooling & slowing inflation. With total household debt servicing costs pushing to record levels our view is the RBA should and will soon pause. US financial problems add to the case.

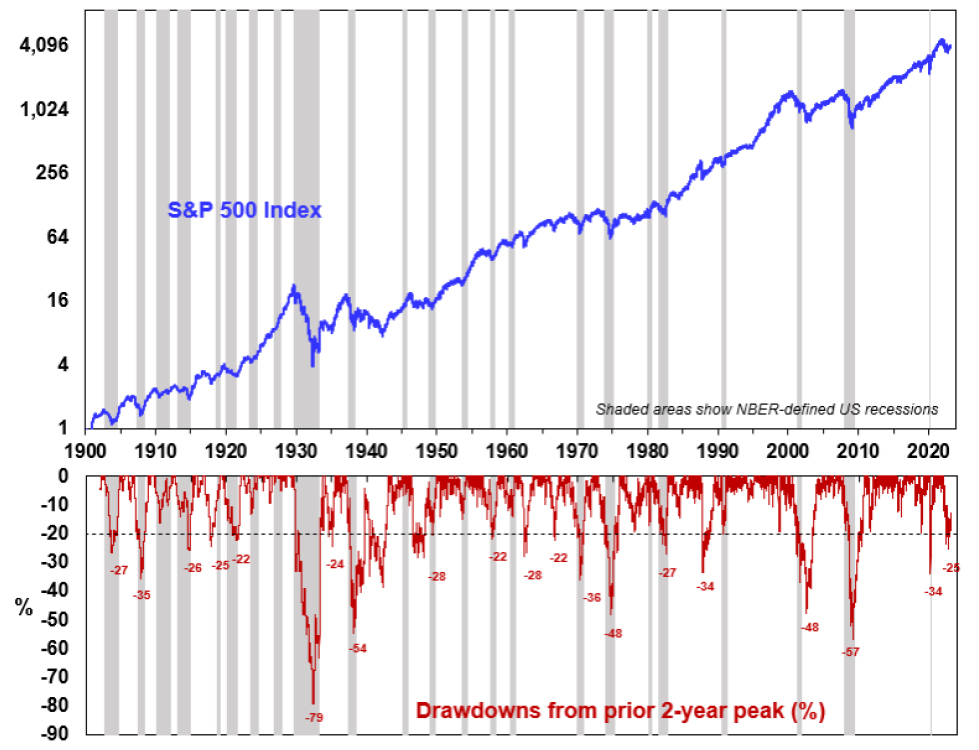

What is the risk of recession?

This will likely be critical to how shares perform this year as the historical record shows that deep bear markets in US (and Australian) shares are invariably associated with US recessions. See the next chart. While the risk of recession has receded in Europe (with the collapse in gas prices) it remains high in the US with various leading indicators – including inverted yield curves (where short term interest rates are above long term yields) – warning of a high risk of US recession in the next 6-12 months. Problems in the financial system are adding to this risk which could easily push US shares down beyond the 25% top to bottom fall seen last year. However, if the Fed soon stops tightening a US recession could still be averted or it could be mild which would limit further downside in US shares.

Equity Bear Markets and Recessions

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

In Australia, the risk of recession is high. But our base case is that it will be avoided thanks to strong business investment, Chinese reopening and providing the RBA soon stops hiking and US financial contagion is limited.

What should all this mean for investors?

We see shares being stronger on a one-year view as inflation falls taking pressure of central banks hopefully enabling economies to avoid a deep recession. However, right now shares are at risk of more downside until some of the issues around the US financial system, inflation, recession and short-term interest rates are resolved. There are several implications for investors:

-

Unlike last year, investment in government bonds should provide more protection for investors as bond yields are now higher and have potential to fall if worries of recession rise as we saw in the last week.

-

Non-US shares are likely to outperform US shares as they are trading on lower price to earnings multiples and have a lower exposure to the tech sector. This includes the Australian share market.

-

For short term investors it’s a time to be cautious.

-

However, while times like these can be stressful, for superannuation members and most investors the best approach is to stick to basic investment principles. These things are worth keeping in mind:

-

share market pullbacks are healthy and normal – their volatility is the price we pay for the higher returns they provide over the long term;

-

it’s very hard to time market moves so the key is to stick to an appropriate long-term investment strategy;

-

selling shares after a fall locks in a loss;

-

share pullbacks provide opportunities for investors to invest cheaply;

-

shares invariably bottom with maximum bearishness;

-

Australian shares still offer attractive income versus bank deposits; &

-

to avoid getting thrown off a long-term strategy – it’s best to turn down the noise around all the negative news flow.

Source: AMP Capital March 2023

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.

Nine key lessons for today from the 1970s, 80s and 90s

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

IntroductionIn 1981 on a holiday with my parents to Hawaii we got into a discussion with some Americans about their new President, Ronald Reagan, and they said he had to deliver some tough economic medicine after years of policy mismanagement. At the time I dismissed them, but as

Read MoreDr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

Introduction

In 1981 on a holiday with my parents to Hawaii we got into a discussion with some Americans about their new President, Ronald Reagan, and they said he had to deliver some tough economic medicine after years of policy mismanagement. At the time I dismissed them, but as the years went by I concluded that they had a point. The 1970s were an economic mess as inflation was allowed to get out of control. In fact, things were so bad that there was a wave of nostalgia for the 1950s and early 60s when things seemed a lot better – starting with American Graffiti, Happy Days, Laverne and Shirley and the rise of retro radio stations playing hits from the 50s and 60s. With inflation surging lately, what lessons can be drawn from the 1970s and its aftermath in terms of today’s problems. This is important because if we don’t learn the lessons of the past, we are bound to repeat them. This is particularly pertinent now as I often hear the comment “why are we so worried about a bit of inflation?” and “why is the RBA inflicting so much pain?”

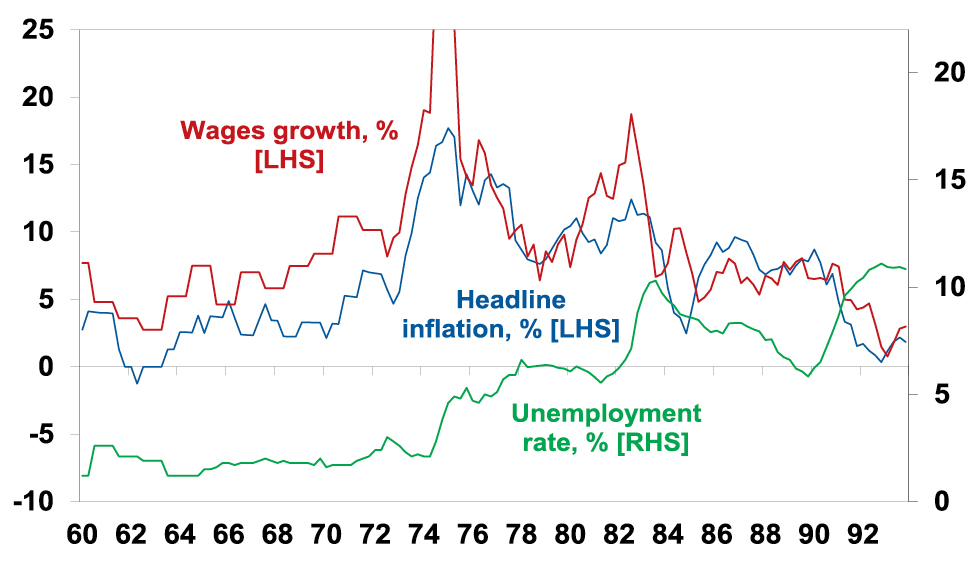

What went wrong in the 1970s?

But first it’s worth a brief recap. From around the mid-1960s inflation started rising. First in the US and then in Australia. It was driven by a combination of tight labour markets, more militant workers demanding higher wages, a big expansion in the size of government, disruption from the Vietnam War, easy monetary policies, social unrest and years of industry protection reducing competition and pushing up prices. It really blew out after the OPEC oil embargo of 1973 and the second oil shock after the Iranian revolution of 1979. The surge in inflation came in waves, reaching double digit levels. It also combined with frequent recessions as policy makers tightened monetary policy in response to high inflation but were too quick to ease when growth slumped only to see inflation take off again driving more tightening and another economic downturn. The end result was a decade of high inflation, high unemployment and slow economic growth from which it took a long time to recover. For investors it was bad as high inflation meant high interest rates, high economic volatility & uncertainty and reduced earnings quality all of which demanded higher risk premiums to invest (& low PEs). The 1970s were one of the few decades to see poor real returns from both shares and bonds.

Aust inflation, wages grth & unemployment, 1960 – early 90s

Source: ABS, AMP

So what broke it?

The malaise ultimately ended after voters turned to economically rationalist political leaders – like Thatcher, Reagan and Hawke and Keating in Australia. The policy response involved:

-

tight monetary policy which drove severe recessions, ultimately culminating in inflation targeting;

-

supply side reforms like deregulation, privatisation & competition laws to make it easier for the economy to meet demand;

-

this was aided by globalisation and then in the late 1990s the tech boom – which boosted the supply of low-cost goods and services;

-

in Australia, the prices and incomes Accord between Government, unions and business helped break the wage price spiral at the time.

This all broke the back of inflation with some in the 2000s calling it dead.

Key lessons

There are several lessons from the malaise of the 1970s and its aftermath and early 1990s recession in Australia for the inflation problem of today:

1. What won’t work. First, the experience of the 1970s and 1980s provides a clear list of things that won’t work to solve the problem:

-

Higher wage growth to keep up with inflation – this just perpetuates high inflation making it harder to get back down.

-

Price controls – these were tried, eg, in the early 1970s in the US. But they restrict supply and when removed inflation was worse than ever.

-

Replacing the RBA Governor – doing this mid-way through the problem would risk shaking confidence in the RBA’s anti-inflation commitment at the worst time likely resulting in even higher interest rates. The US saw something similar in the 1970s when it replaced William Martin at the Fed with Arthur Burns which just perpetuated high inflation.

-

·Raise the RBA’s inflation target – this would also reduce confidence in its ability to get inflation down and mean higher interest rates.

-

Shift responsibility for inflation control back to government – this sounds fine in theory as governments have more levers to pull (eg it could impose a 1% temporary income tax surcharge to cool demand which would spread the load more fairly beyond those with a mortgage). But unfortunately, politicians have shown an inability to inflict the pain necessary to slow inflation. So, it doesn’t work in practice. It was the way things were done in Australia in the 1970s and its failure led to the widespread adoption of central bank independence focussed on meeting an inflation target.

2. Containing inflation expectations is key. Once inflation takes hold it gets harder to squeeze out. This relates to “inflation expectations”. Once inflation has been high for a while consumers and businesses expect it to stay high and so behave in ways – via wage demands, price setting and acceptance of price rises – that perpetuate it. A wage price spiral is a classic example of this where prices surge, workers demand wage rises to compensate which boosts costs & drives a new round of sharp price rises. This is an example of the “fallacy of composition” – while it is rational for an individual to demand a wage rise to match inflation if all workers do so it just leads to a further surge in prices.

3. Whether its supply or demand, central banks have to respond. While the initial impetus to a surge in inflation may be constrained supply if it occurs when demand is strong or goes on for too long, central banks still have to respond to cool demand and signal they are serious about containing inflation. Central banks failure to do this after the 1973 OPEC oil shock contributed to inflation getting entrenched in the 70s.

4. Avoid stop go monetary policy. There is a danger in easing monetary policy too early in a downturn if inflation expectations have not been tamed. This occurred in the 1970s with inflation slowing and central banks easing as growth slowed but inflation soon rising even higher. This underpins talk central banks will keep rates “higher for longer”.

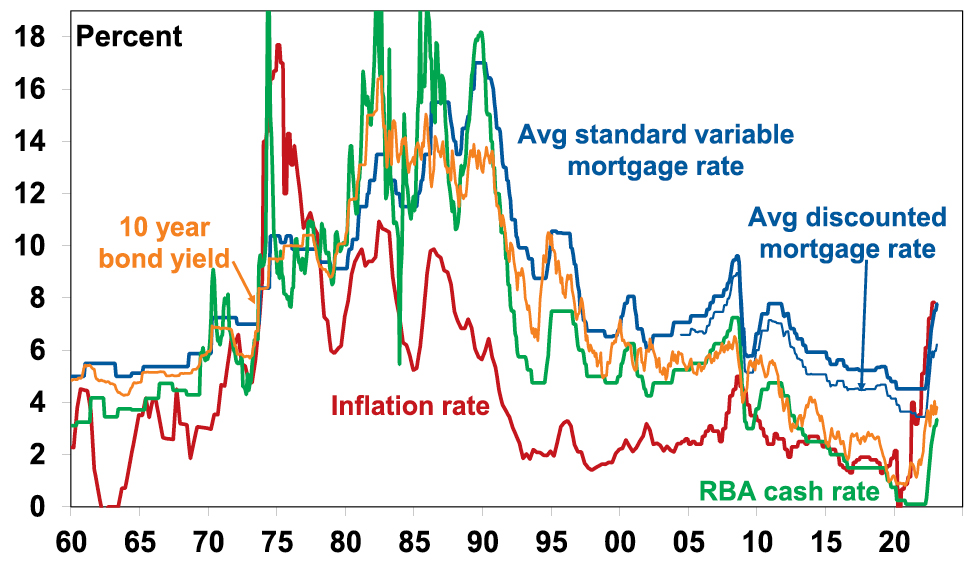

5. Entrenched high inflation will mean entrenched high interest rates. This is because investors will start to demand compensation for the fall in the real value of their savings by demanding higher rates. So interest rates rose through the 1970s into the 1980s. And this of course weighs on the valuation of shares and property. 10-year bond yields of around 3.5% to 4% are fine if investors expect inflation will fall to say 2-3% but if they believe inflation will stay high at 6-8% then they are too low.

Sustained high inflation = high interest rates

Source: ABS, AMP

6. Entrenched high inflation is bad for the economy. Because it distorts economic decisions it can cut economic growth as in the 1970s, add to economic uncertainty which hampers investment & boost inequality.

7. Once entrenched high inflation risks requiring a deep recession to remove it. This was seen in the deep recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s in Australia which saw double digit unemployment. This was because by the late 1970s inflation expectations in the US as measured by the University of Michigan consumer survey were running around 10% following years of very high inflation making it harder to get inflation down. Australia was likely similar.

8. Governments should focus on the supply side. The practical inability of governments to adjust fiscal policy much to control inflation means the best it can do in the short term is not add to the problem and this means reducing budget deficits and limiting new spending. Longer term there is a lot that government can do to help control inflation and its all about supply side reform to make the economy work more smoothly, ie deregulate, cut back government and competition reforms. Unfortunately, the political appetite for such reforms is low.

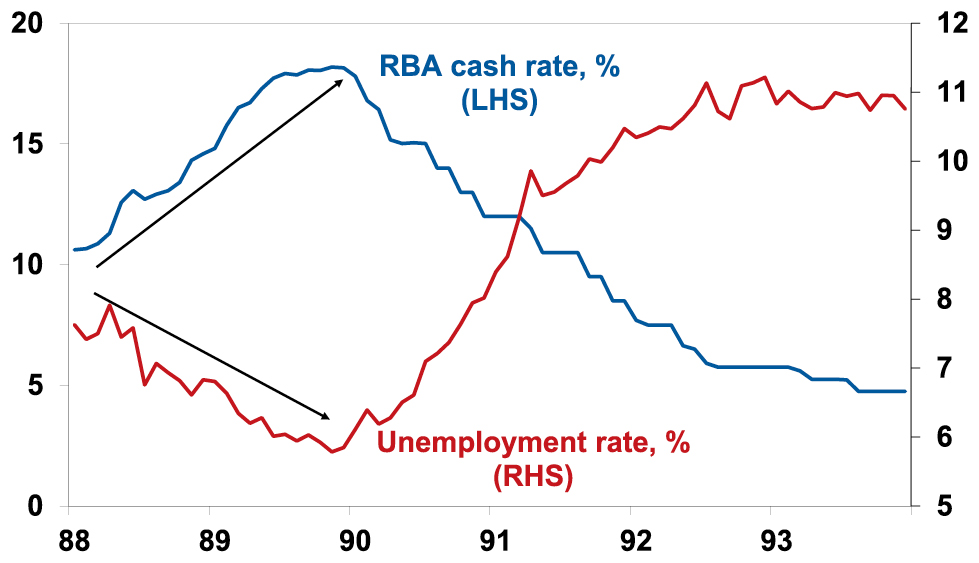

9. Monetary policy operates with a lag. The early 1990s recession showed monetary policy works with a lag. This seems contradictory to the fourth point above but highlights the risk of overtightening. The lags arise as it takes time for rate hikes to be passed on to borrowers, that to slow spending and then for slower demand to lead to less employment and the flow on of this back to households and for all of this to cool inflation. This can take 12 months or more. So just looking at inflation and jobs data can be misleading as they are lagging indicators. In the late 1980s the RBA kept hiking and unemployment kept falling. But by early 1990 it was clear it had gone too far.

RBA rate hikes & unemployment in the late 1980s/early 1990s

Source: ABS, RBA, AMP

So what does it all mean for today?

The good news is that this is not 1980 and more like the early 1970s: inflation expectations are low; there is no evidence of a wage price spiral, notably in Australia; supply bottlenecks, freight costs and surging money supply which led inflation are now reversing; and high household debt ratios compared to the 1970s should make monetary policy more potent. But the lessons from the 1970s explain why central banks are so fearful of letting inflation get out of control and also the difficult balancing act facing them. As RBA Governor Lowe said they “are managing two risks…not doing enough [resulting in high inflation persisting & proving costly later] [and] that we move too fast, or too far” and trigger recession. Balancing these two risks is seen as resulting in a narrow path to low inflation and the economy continuing to grow. But what is too much or too little tightening is a judgement call. The RBA’s view has become more hawkish after the December quarter CPI and is signalling at least two more rate hikes and money markets and the consensus of economists have moved to reflect this with consensus rate expectations rising above 4%. Our view is that the RBA risks doing too much given the high vulnerability of a significant minority of indebted Australian households and that the impact of past rate hikes is just being masked by normal lags accentuated by revenge spending associated with reopening. Signs of slowing consumer spending and jobs growth along with there still being no evidence of a wages breakout in Australia are consistent with this. As such, it risks a re-run of the late 1980s/early 1990s experience where Australia was inadvertently knocked into a deep recession as the lagged impact of rate hikes took time to show up. So, while we believe rates are close to the top, the RBA’s tough guidance means that the risks are skewed to the upside. Further evidence of a slowing consumer and jobs data are necessary to cause the RBA to rethink so upcoming retail sales and jobs data are critical in this.

So what does it all mean for today?

The good news is that this is not 1980 and more like the early 1970s: inflation expectations are low; there is no evidence of a wage price spiral, notably in Australia; supply bottlenecks, freight costs and surging money supply which led inflation are now reversing; and high household debt ratios compared to the 1970s should make monetary policy more potent. But the lessons from the 1970s explain why central banks are so fearful of letting inflation get out of control and also the difficult balancing act facing them. As RBA Governor Lowe said they “are managing two risks…not doing enough [resulting in high inflation persisting & proving costly later] [and] that we move too fast, or too far” and trigger recession. Balancing these two risks is seen as resulting in a narrow path to low inflation and the economy continuing to grow. But what is too much or too little tightening is a judgement call. The RBA’s view has become more hawkish after the December quarter CPI and is signalling at least two more rate hikes and money markets and the consensus of economists have moved to reflect this with consensus rate expectations rising above 4%. Our view is that the RBA risks doing too much given the high vulnerability of a significant minority of indebted Australian households and that the impact of past rate hikes is just being masked by normal lags accentuated by revenge spending associated with reopening. Signs of slowing consumer spending and jobs growth along with there still being no evidence of a wages breakout in Australia are consistent with this. As such, it risks a re-run of the late 1980s/early 1990s experience where Australia was inadvertently knocked into a deep recession as the lagged impact of rate hikes took time to show up. So, while we believe rates are close to the top, the RBA’s tough guidance means that the risks are skewed to the upside. Further evidence of a slowing consumer and jobs data are necessary to cause the RBA to rethink so upcoming retail sales and jobs data are critical in this.

Source: AMP Capital February 2023

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.

Seven key charts for investors to keep an eye on

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

IntroductionShares had a strong start to the year seeing gains into early February around or above what we expect for the year as a whole. But we still expect that it will be a volatile year given that: the process of getting inflation back down won’t be smooth;

Read MoreDr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital

Introduction

Shares had a strong start to the year seeing gains into early February around or above what we expect for the year as a whole. But we still expect that it will be a volatile year given that: the process of getting inflation back down won’t be smooth; the topping process in central bank rates will take time with setbacks along the way as we have seen for both the Fed and the RBA recently; recession risks are high; raising the US debt ceiling around the September quarter won’t be smooth; and geopolitical risks around Ukraine, China (as highlighted by the balloon over the US) and Iran (which is getting close to nuclear weapon breakout capacity) are significant. With shares becoming overbought after the new year rally and seasonality turning less positive, shares both globally and in Australia are vulnerable to more of a pull back in the short term. This note updates seven charts we see as critical for the investment outlook.

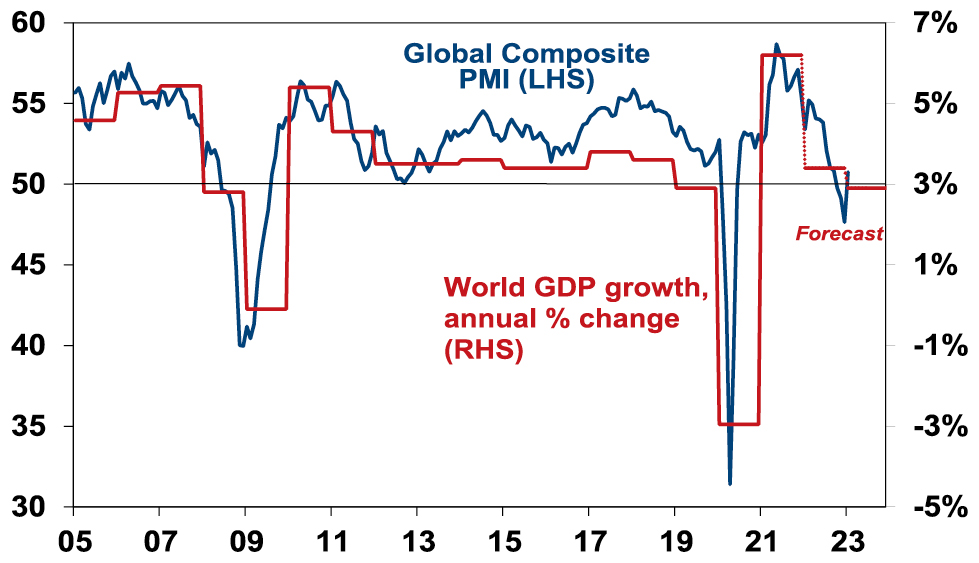

Chart # 1 – global business conditions PMIs

Whether share markets fall back to new lows and resume the bear market in US and global shares that started last year will be crucially dependent on whether major economies slide into recession and, if so, how deep that is. Our assessment is that global growth will be around 2.5-3% this year. Global Purchasing Managers Indexes (PMIs) – surveys of purchasing managers at businesses – will be a key warning indicator.

Global Composite PMI vs World GDP

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

They have slowed but are not at levels associated with recession. In January they rose, helped by China’s reopening. So far, they still look ok.

Chart 2 (and 2b) – inflation

A lot continues to ride on how far key central banks raise interest rates. And the path of inflation will play a key role in this. Recently the news has been better with inflation rates in key countries rolling over. US inflation is well down from its high last year and our US Pipeline Inflation Indicator – reflecting a mix of supply and demand indicators – has been falling, pointing to a further fall in inflation. The key is that US inflation continues to fall – if so, this should allow the Fed to stop hiking in either March or May and it could find itself needing to cut rates from later this year.

AMP Pipeline Inflation Indicator

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

Our Australian Pipeline Inflation Indicator also suggests that Australian inflation has peaked and will fall through this year, albeit Australian inflation and the RBA are lagging the US and the Fed.

Australia Pipeline Inflation Indicator

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

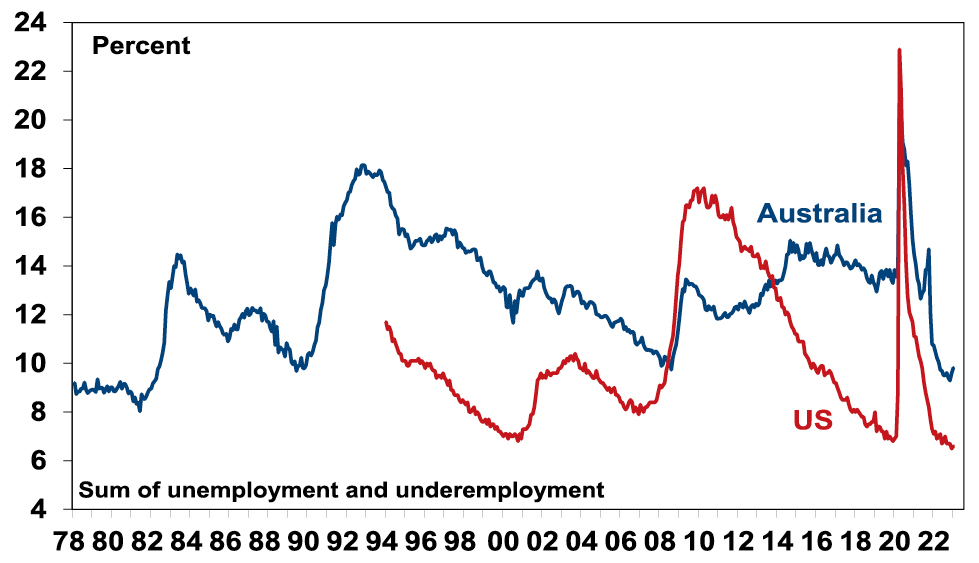

Chart 3 – unemployment and underemployment

Also critical is the tightness of labour markets as this will help drive wages growth. If wages growth accelerates too far it risks locking in high inflation with a wage-price spiral which would make it hard to get inflation down. Unemployment and underemployment are key indicators of this. Both remain very low in the US & Australia (putting upwards pressure on wages), but there is some evidence that labour markets have seen the best and may now be slowing. And wages growth in the US looks to have peaked.

Labour market underutilisation rates

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

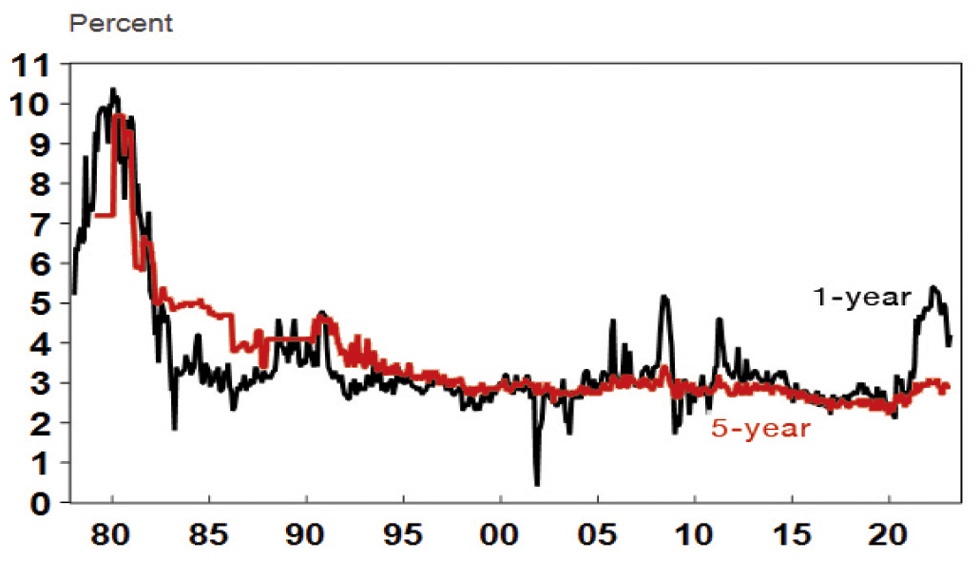

Chart 4 – longer term inflation expectations

The 1970s experience tells us the longer inflation stays high, the more businesses, workers and consumers expect it to stay high & then they behave (in terms of wage demands, price setting & tolerance for price rises) in ways which perpetuate it. The good news is that short term (1-3 years ahead) inflation expectations have fallen lately in the US and longer-term inflation expectations remain low. The latter is consistent with 2% or so inflation & suggests the job of central banks should be far easier today than say in 1980 when the same measure was around 10% and deep recession was required to get inflation back down. The key is that it stays low.

US University of Michigan Consumer Inflation Expectations

Source: Macrobond, AMP

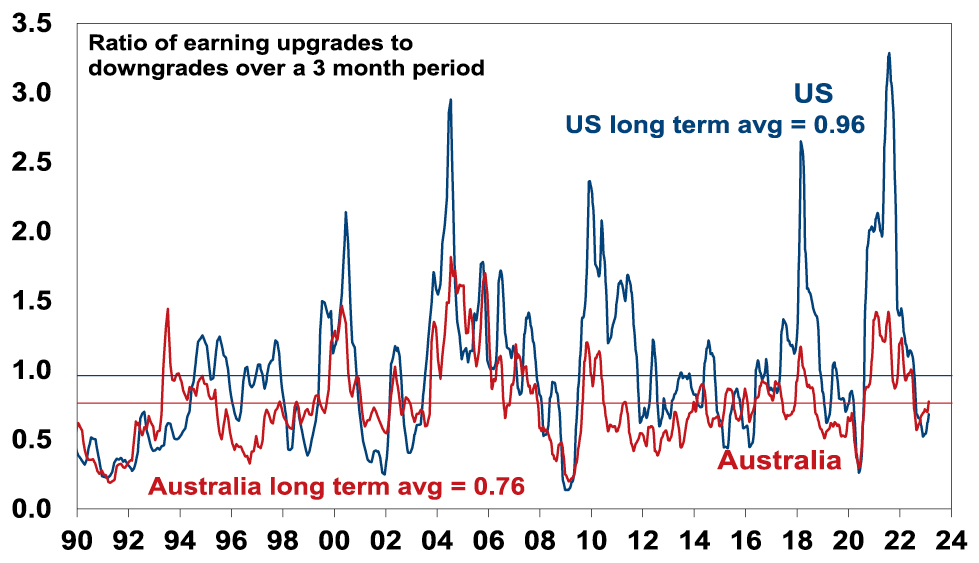

Chart 5 – earnings revisions

Consensus earnings growth expectations for this year are around 11% for the US and around 7% for Australia. They look a bit too high, but a deterioration on the scale seen in the early 1990s, 2001-03 in the US and 2008 would be bad news. So far so good.

Earnings Revision Ratio

Source: Reuters, AMP

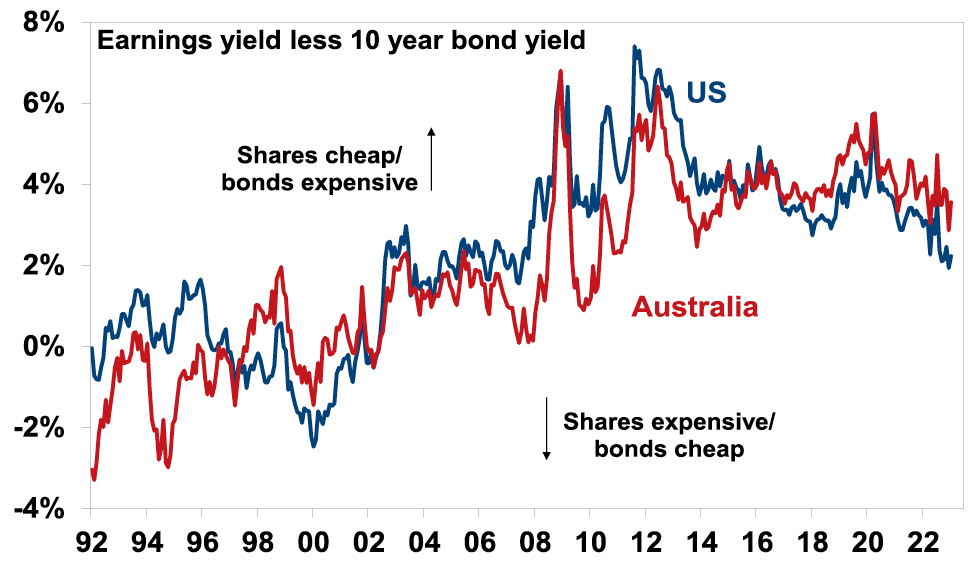

Chart 6 – the gap between earnings and bond yields

Over the last year rising bond yields have weighed on share market valuations. As a result, the gap between earnings yields and bond yields (which is a proxy for shares’ risk premium) has narrowed to its lowest since the GFC in the US. Compared to the pre-GFC period shares still look cheap. Australian share valuations look a bit more attractive than those in the US though helped by a higher earnings yield. Ideally bond yields need to continue to decline and earnings downgrades need to be limited in order to keep valuations okay.

Shares still offer a reasonable risk premium over bonds

Source: Reuters, AMP

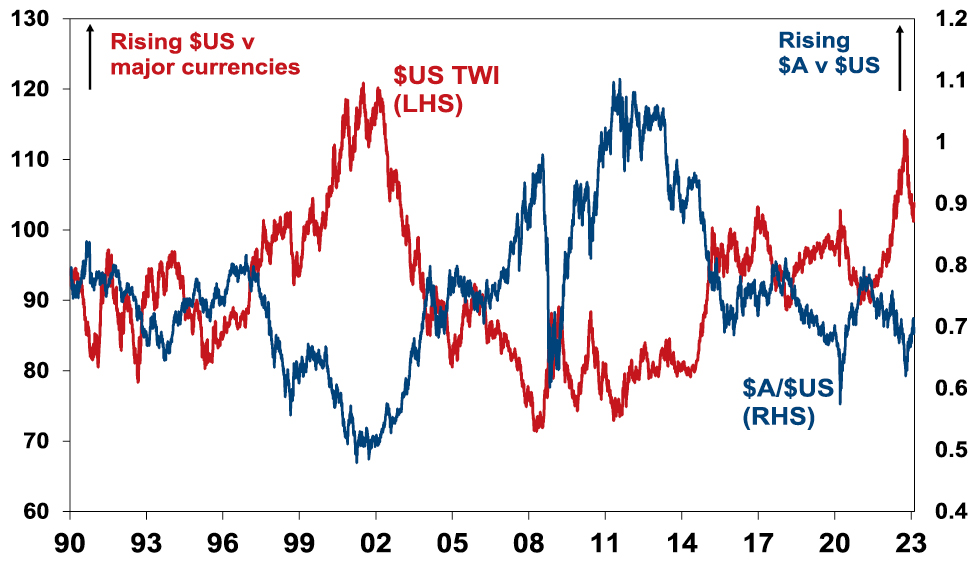

Chart 7 – the US dollar

The US dollar is a counter cyclical currency, so big moves in it are of global significance and bear close watching as a key bellwether of the economic and investment cycle. Due to the relatively low exposure of the US economy to cyclical sectors, the $US tends to be a “risk-off” currency, ie, it goes up when there are worries about global growth and down when the outlook brightens. Last year the $US surged with safe haven demand in the face of worries about recession and war and more aggressive monetary tightening by the Fed. Since September though it has fallen back as inflation and Fed rate hike fears have eased and geopolitical risks receded a bit. A further fall in the $US would be consistent with our reasonably upbeat view of investment markets this year, whereas a sustained new upswing would suggest it may be vulnerable. So far so good.

The $US v major currencies & the $A

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

Source: AMP Capital February 2023

Important note:While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.